1. ACO Awards: An Evening at the Stunning Junction Craft Brewery

Catherine Nasmith

As chair of ACO's Awards Committee, I couldn't be prouder of the nominations we received and the chance to celebrate so much amazing work going on across Ontario. We're celebrating in an amazing new venue, The Junction Craft Brewery

Tickets still available http://acontario.ca/event.php?eid=22

Awards Night is almost here!

It's an exciting year for the ACO Heritage Awards. We received 30 excellent nominations (more than ever before). We've chosen a new venue that's an excellent example of adaptive reuse of a previously neglected heritage building (with special tours by the building's owner), we'll have CBC national reporter Philip Lee-Shanok as our MC, and we're not telling you who the winners are before awards night, with two exceptions (stay tuned for another email, we'll be announcing two of our winners on Monday).

Why the changes? We wanted to make the awards more accessible (with a much lower ticket price), we wanted to explore a new historic building, and we wanted to celebrate all of the great work that's being done across the province. We hope you feel as excited about the awards as we are! They will be presented at an awards party and ceremony at Junction Craft Brewing in Toronto (formerly the Symes Road Destructor, built 1934) on Thursday October 11. You can click on the image below or BUY TICKETS HERE.

and the 2018 Award Nominees are...

A.K. Sculthorpe Award for Advocacy Nominees:

Kathy Gastle & The Heritage Foundation of Halton Hills, Halton Hills

For their ongoing commitment to heritage preservation, fundraising, and raising public awareness of heritage issues to support heritage projects in Halton Hills

Michael Kirkland, Toronto

For helping decision makers in the City of Toronto understand the importance of Upper Canada's First Parliament Buildings (1798) and create a meaningful plan for the site that would acknowledge its history

The Working Centre (founders Joe & Stephanie Mancini), Kitchener

For giving new life to eight heritage buildings in downtown Kitchener, demonstrating to the local community that it’s possible to have adaptive reuse without gentrification

Margaret Zeidler and the tenants of 401 Richmond Street West, Toronto

For leading an important advocacy project to have a new property tax class created for creative hubs (the new Creative Co-Location Facilities tax class)

ACO Media Award

Any Other Way: How Toronto Got Queer (Coach House Books)

For chronicling the fascinating history of gay and lesbian life in Toronto in a one of a kind historical record

Simon Brothers and Dean Robinson, Stratford

For creating the documentary film GRAND TRUNK, A City Built on Steam, Stratford, Ontario, raising awareness of the importance of Stratford's huge locomotive repair shops (1907-09) to the city's history

Edward Butts, Guelph

For writing 30+ books that share and encourage a love of history and heritage, including many for young readers, and for bringing local history to life with his engaging columns in the Guelph Mercury

Jeff Fournier, North Bay

For his successful effort to save the the Dionne Quintuplets’ birth home and artefacts through extensive lobbying, fundraising, and using social media to attract the attention and support of thousands worldwide

Katherine Taylor, Toronto

For her blog One Gal’s Toronto: Unearthing the stories of the city’s forgotten people and places, full of engaging stories of Toronto's built and cultural heritage meticulously researched and shared

ACO Toronto's TOBuilt

For creating a significant heritage resource through its crowd-sourced database of buildings and structures in Toronto, establishing a precedent for a province-wide architectural database

The Ward Uncovered: The Archaeology of Everyday Life (Coach House Books)

For bringing to life a neighbourhood that was long ago erased from contemporary Toronto and aiming to recover The Ward’s place within Toronto’s history

ACO NextGen Award

Sampoorna Bhattacharya, Richmond Hill/Ottawa

For her volunteer leadership and her commitment to the study and application of heritage conservation, not only for its historical value, but for the future sustainability of the planet

Eric Arthur Lifetime Achievement Award

Janet Hunten, London

For her contributions to the heritage sector in London over more than 40 years, both professionally and as a volunteer. At age 90, she is still involved and a great asset to the City of London and the wider heritage community.

James D. Strachan Award for Craftsmanship

Eve Guinan, Eve Guinan Design & Restoration, Toronto

For her extensive body of work restoring stained glass windows since 1985, including churches, cathedrals, museums, historic homes and parliamentary buildings, and her contributions to the conservation of stained glass in Ontario

Spire Restoration at Ste. Anne Church, Tecumseh

For demonstrating excellent restoration practices and overcoming great challenges to undertake a precise, technically difficult restoration of a significant community landmark

Margaret and Nicholas Hill Cultural Heritage Landscape Award

Belle Vue Conservancy, Amherstburg

For its tireless work to save a historic at-risk property and persuade the local community to see its potential, resulting in this beautiful local landmark being restored to become an event space and garden for public use

The Friends of Allan Gardens: Refresh, Toronto

For creating a bold and holistic Vision document that examines whether Allan Gardens is evolving in a way that honours its rich cultural heritage, and contributes to the livability and inclusivity of 21st century Toronto

Leaside Matters, Toronto

For undertaking several well-organized and well-publicized projects that bring Toronto into better touch with Leaside as a cultural landscape with a unique history and sense of place

The Palmerston Railway Museum and the Palmerston Lions Heritage Park, Palmerston

For restoring Palmerston's 1871 train station and developing the Heritage Park, while including numerous local volunteers to bring the historic site to its Grand Trunk-era glory

Mary Millard Award for Special Contributions

Phillip H. Carter, Architect and Planner, Toronto

For his decades working in support of built heritage, his leadership in the Port Hope branch of ACO and Port Hope LACAC over several years, his work on many heritage publications, and his work to to help preserve small towns

Stephanie Mah, Toronto

For her enormous contributions to ACO in several roles while still in the early years of her career. Stephanie has assisted with ACO's branding, graphic design and photography, social media and outreach, and has demonstrated exceptional volunteer leadership.

Paul Oberman Award for Adaptive Reuse (Corporate)

Core Urban Inc., Hamilton

For its exemplary commercial adaptive re-use projects in Hamilton, including The Empire Times (2014), The Textile Building (2016), Templar Flats (2017), and The Alley (occupancy fall 2018), in which original features such as wood floors, tin ceiling, and three ceiling domes have all been carefully restored.

Junction Craft Brewery and PLANT Architect Inc. - Junction Craft Brewery in the Symes Road Destructor, Toronto

For the impressive adaptive reuse of a venerable heritage building by a business. They retained the stunning Art Deco design and industrial character of the site, while repurposing it to feature a technically demanding manufacturing system and a polished business venture.

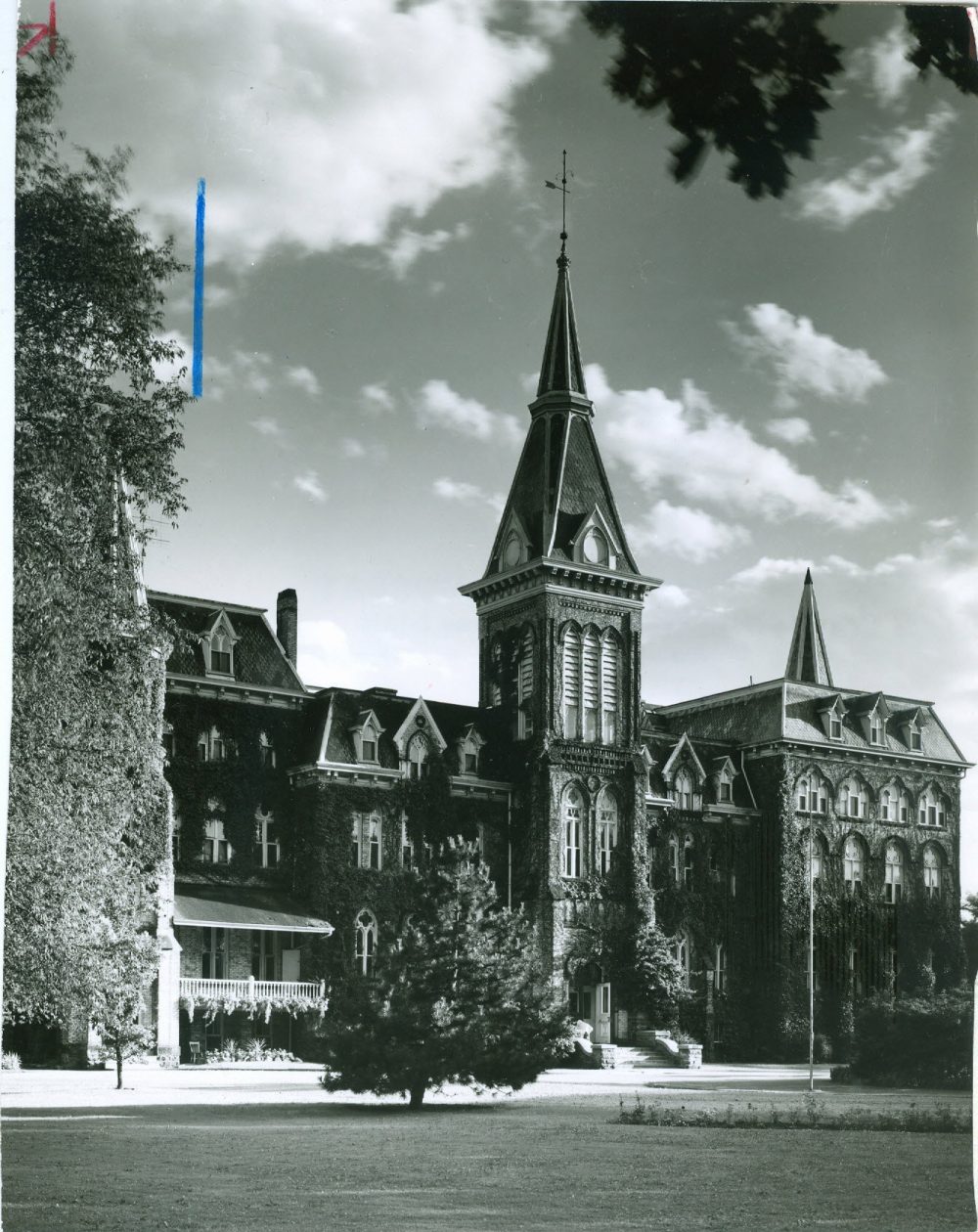

One Spadina Crescent / The Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Toronto

For establishing a new gateway to the University of Toronto campus at one of Toronto's most prominent and historic addresses. The recent renewal of the south-facing 19th century Gothic Revival building and contemporary addition is a showcase for the city and an international focal point for education, research, and outreach on architecture, art, and the future of cities.

Paul Oberman Award for Adaptive Reuse (Small Scale/Individual/Small Business)

Schmaltz Appetizing (owners Robert Wilder and Anthony Rose), Toronto

For setting an exceptional example of a small business respecting an existing historic commercial building and re-imagining it in a creative way to suit a new use, brilliantly blending old and new and maintaining its heritage despite having no obligations to do so.

Peter Stokes Restoration Award (Corporate)

The Opinicon (owner Fiona McKean), Elgin

For bringing an abandoned fishing resort (built 1870 and 1901) back to life and in doing so, revitalizing a community. Owner Fiona McKean redeveloped the resort through sheer guts, the skills and tenacity of local talent, and the hopes and dreams of thousands of past and current guests. McKean took great care to incorporate heritage aspects, the desires of the community, and the sustainability of the business to ensure that the cultural heritage embodied in the sprawling grounds was preserved.

Tyrcathlen Partners (owners Kirk Roberts and Peregrine Wood) for The Petrie Building, Guelph

For their restoration of a unique 1882 building with a highly ornamented, stamped-zinc facade, at enormous cost and effort, bringing a dilapidated treasure back to life. The New Petrie Building joins Tyrcathlen's earlier projects, the Granary Building and Boarding House Arts, as excellent examples of how innovative partnerships and solutions save heritage buildings and transform their use.

Peter Stokes Restoration Award (Small Scale/Individual/Small Business)

Tom Plue, Sky-High Historical Restoration & Consulting, Roseneath

For restoring the cupola on 100 University Avenue East in Cobourg, a building of architectural and historical significance. Despite rotted historic elements and animal infestation due to neglect, Plue restored the cupola using creative methods to solve problems caused by a lack of maintenance that would normally lead to the loss of original elements.

Andrew Pruss, ERA Architects, Toronto

For the rehabilitation of the Sony Centre for the Performing Arts' cantilevered canopy, located above the entrance to the theatre. This involved the removal of new additions and a return to the aesthetic of the original 1960 design, while updating the lighting to contemporary standards. The project was completed in February of 2018.

John Rutledge Architect (Blyth, ON) for Benmiller Community Hall, Goderich

For rehabilitating local public school Benmiller S.S. No. 2 (built 1880), providing barrier-free accessibility and needed upgrades to outdated facilities. The refurbished Benmiller Hall (which reopened in 2017) sympathetically balances new and old to create contextual harmony for continued community use.

2. Heritage Toronto Award Nominations

Press Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

NOMINEES ANNOUNCED

FOR 2018 HERITAGE TORONTO AWARDS

August 2, 2018 (Toronto, Ont.) – Heritage Toronto is pleased to announce the 53 nominees for the 2018 Heritage Toronto Awards. The inspiring work ranges from a Chinese Canadian Archive to "dirty" mansions to new parks, and spotlights subjects such as the Red Scare, our Whiskey Kings and the Underground Railroad in Toronto. Nominees are being recognised for their extraordinary contributions to Toronto's heritage in five categories: Community Heritage, Public History, Historical Writing: Short Publication, Historical Writing: Book, andWilliam Greer Architectural Conservation and Craftsmanship.

The longest-running heritage awards in Canada, the 44th Heritage Toronto Awards will be celebrated on Monday, October 29, at The Carlu.

THE NOMINEES

Five volunteer-based organizations are nominated for the Community Heritage Award which features a $1,000 cash prize. The group includes Ireland Park Foundation, recognized for its commemorative public space dedicated to the Irish famine migrants of 1847, and its ongoing work to promote the history of the Irish in Canada; and RISE UP! A Feminist Archive, a digital archive dedicated to fostering research and inter-generational conversations, and inspiring activism for future social change.

Among the 18 Public History Award nominees are Berczy Park, the site of razed historical buildings that was first converted into parking and now serves as a public space for evolving community needs; Historica Canada's first animated Heritage Minute on Kensington Market that captures the newcomer-centered history of this vibrant and culturally diverse neighbourhood in the downtown core; and Driftscape, a free mobile application that uses content from arts and cultural groups to produce place-based experiences in a new collaborative multimedia approach.

The 18 nominees in the Book category range from Any Other Way: How Toronto Got Queer, a richly illustrated history of how individuals and community networks transformed Toronto from a conservative place into a city that has led the way in queer activism; to Frontier City: Toronto on the Verge of Greatness, a collection of conversations with political candidates from across Toronto on how they energize their communities to address local issues of poverty, violence, racism, and drugs. Other nominees examine Toronto's music scene inLightfoot, a biography of one of Canada's greatest songwriters, and the city's most fascinating and shadowy deaths in The Toronto Book of the Dead.

For the time-pressed, this year's seven Short Publication Award nominees offer quick but enthralling reads. Nominees explore the history of Toronto's iconic music venue and its planned multi-year renovations in the pamphlet Massey Hall – Shine a Light; the enduring symbolic appeal of the maple leaf to Canadian identity in the exhibit catalogue Maple Leaf Forever; and the accusation of communist allegiance against one of Canada's most powerful media moguls in the article Historicist: Ted Rogers, Communist?.

Highlighted among the five exemplary projects nominated in the William Greer Architectural Conservation and Craftsmanship category are the adaptive reuse of Lakeshore Psychiatric Hospital's administrative building into Humber College's new Centre for Entrepreneurship; the restoration of glass work in the Keg Mansion restaurant, formerly the stately home of one of Canada's most famous families; and the conversion of a rare Chicago School-style building in Toronto that housed a succession of furniture stores into the WE Global Learning Centre.

A full nominee list, by category and with descriptions, is available at the 2018 Awards Website. As part of the Awards Ceremony, the Heritage Toronto Board is pleased to also present a Special Achievement Award and a Heritage Toronto Volunteer Service Award with recipients to be announced to the media on September 27.

Heritage Toronto is a charity and agency of the City of Toronto that celebrates and commemorates the city's rich heritage and the diverse stories of its people, places, and events.

EVENT DETAILS

Tickets to the event are $95 ($70 for Heritage Toronto members), and can be purchased online at heritagetoronto.org or by phoning 416-338-1338. This event is Heritage Toronto's major fundraiser of the year, raising monies in support of its public programming.

|

VENUE

|

The Carlu (444 Yonge Street West, Toronto)

|

|

MAYOR'S RECEPTION

|

5:30 PM

|

|

AWARDS CEREMONY

|

7:00 PM

|

- 30 -

Reporters, photographers and videographers are welcome to attend the Awards.

Media Contact: Lucy Di Pietro, Manager, Marketing & Communications

416-338-1339

lucy.dipietro@toronto.ca

3. Heritage Surveys & Community Engagement Event

Heritage Preservation Services

City Planning is undertaking a Feasibility Study on developing a city-wide heritage survey and is exploring how best to engage residents in order to enrich our understanding of the City’s evolving history and character. Join Heritage Preservation Services staff and Toronto’s Community Preservation Panels to share ideas on how to broaden engagement by bringing new voices into the planning process.

Guest Speaker:

Janet Hansen, Deputy Manager of the City of Los Angeles Office of Historic Resources, and manager of the multi-year SurveyLA project, the largest citywide survey ever completed in an American city.

Engage, Involve, and Partner: Lessons in Community Engagement from SurveyLA, the City-Wide Heritage Survey of Los Angeles

Panel Discussion:

Panelists will briefly interact with the presentation and spark a Q&A to follow.

- Matti Siemiatycki, Interim Director, School of Cities, University of Toronto

- Allison Bain, Executive Director, Heritage Toronto

- Nadira Pattison, Manager, Arts Services, City of Toronto

Presented by the City of Toronto, City Planning Division and Community Preservation Panels of Toronto Promoting partner: Heritage Toronto

October 15, 2018 —

7:00 pm to 8:30 pm

North York Civic Centre, Council Chambers, 5100 Yonge Street

Free and open to the public

REGISTER NOW

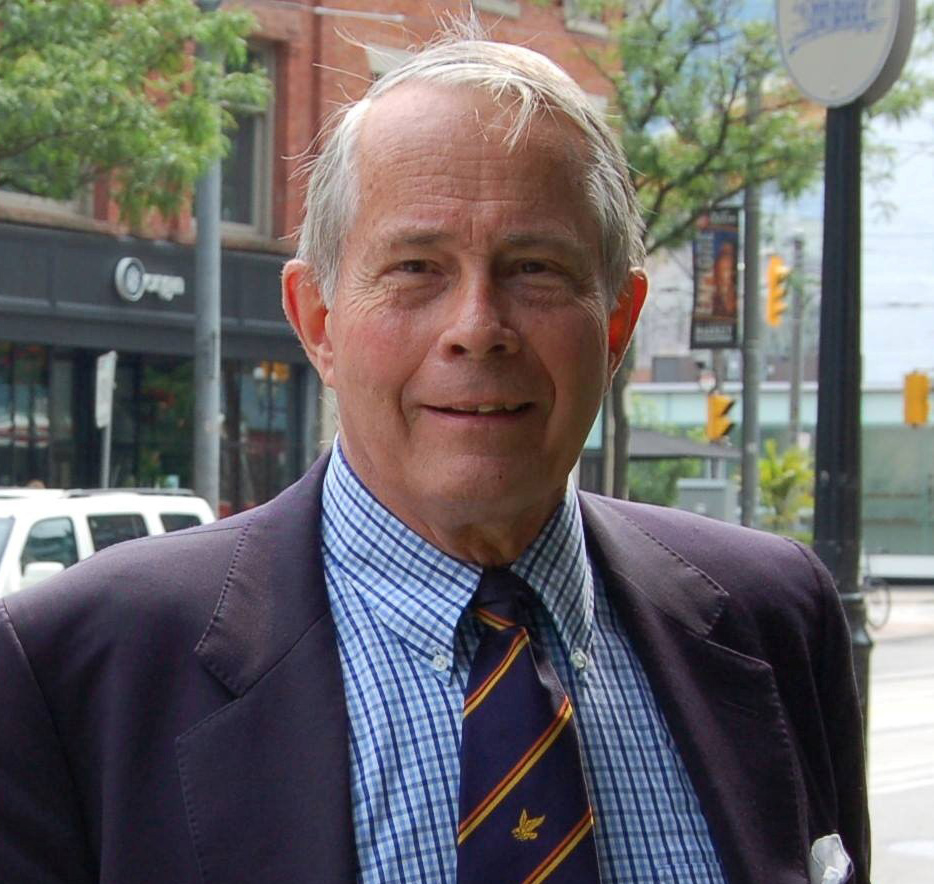

4. A Chance to Listen to the Voice/Thoughts of Stephen Otto on The Gardiner Expressway

Catherine Nasmith/Shawn Micaleff

|

| The late Stephen Otto, taken on Queen Street West, 2016? |

This note crossed my desk this week, and thought many others might be interested in enjoying the voice and thoughts of Stephen Otto, recorded a couple of years back, speaking about the Gardiner Expressway.

Edited note from Shawn Micallef:

A couple years ago I connected a fellow from back home in Windsor, Walter Petrichyn, with Stephen Otto. He was making a film about the Gardiner Expy that, I think, was part of an MFA he was doing at Parsons in NYC. Anyway, they met, and chatted and Walter ultimately made his film. Walter wrote the other day and sent me the entire audio file of his interview with Stephen, plus a “near complete” transcription of it. He also sent me a link to his film.

Here’s the short film:

https://vimeo.com/178943825

Attached is the transcription Walter sent me

The audio file is massive (80mb) and about an hour long, so I can’t attach it here but I put in a google folder so you can listen there, and it can also be downloaded for your own files: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1PL_08JrMoncS9LntdSJHIw0BpZBqMx7t/view?usp=sharing

Editor's Note:

As readers will be aware, Stephen Otto died in April and is much missed by his friends and colleagues. These tapes are a real treat, a chance to listen to him once more.

5. Two Letters re: Chateau Laurier Addition

Peter Coffman, Andrew Waldron

IT'S JUST SO ... T.O. DULL

ReRelax,Ottawa:The Chateau Isn't Falling (June18): Larco Investments engaged Peter Clewes as the architect of the Chateau Laurier addition. In my opinion, this was a mistake.

Not because Mr. Clewes and his heritage architectural consultant, Michael McClelland, are bad architects, but because Larco doesn't appear to understand Ottawa's unique architecture. It is different from the architecture of Toronto, where both architects are more in their comfort zone.

What 1’ve have in the design of the addition to the Chateau Laurier is a decorated shed, on a modernist theme. If the team had unpacked the complexity and sophistication of the original architecture and setting, Larco would be receiving international acclaim. Instead, we are presented with a dull, incompatible box that the architects have even (desperately?) suggested will be invisible in its deference to the grand Chateau: How typically dull Toronto is that!

Ottawa is an intensely romantic and sublime city (politically and in other respects), which is what has unfortunately been ignored in the proposal.

Andrew Waldron, architectural historian, heritage conservationist, author Exploring the Capital: An Architectural Guide to the Ottawa-GatineauRegion

SUBTLE IT'S NOT

Re Relax Ottawa: The Chateau Isn't Falling June 18): Alex Bozikovic's thoughtful defence of the modernist Chateau Laurier addition overlooks a crucial point: Much great modernist architecture is great specifically because it is very site-specific. Think of Frank Lloyd Wright's Fallingwater, cascading down the hillside in tandem with the stream it straddles, or any of Wright's broad, low "Prairiestyle" houses.

By contrast, the modernist box proposed by Peter Clewes squats on the ensemble of Chateau, Parliament, canal,cliffside and river with the sensitivity and subtlety of a jackboot in a flower garden. Modernism acquired a reputation for being heavy-handed: That's not fair, but Mr. Clewes's design shows you exactly why it happened.

PeterCoffman,associate professor, History and Theory of Architecture, Carleton University

Editor's Note:

These two letters were forwarded by Peter Coffman, following the links to Alex Bozikovic's article.

6. Globe and Mail: Low Rise Intensification

Alex Bozikovic

How to remake Toronto

A Norm Li rendering of Toronto firm Batay-Csorba Architects' vision for low-rise, multifamily housing.

BATAY-CSORBA

It’s got a brick façade. It has a sloped roof. And it has space for five families – in comfortable spaces – instead of two narrow houses. This is what the future of Toronto’s house neighbourhoods could look like.

This vision comes from Batay-Csorba Architects, a young and talented Toronto firm. Recently, I wrote about how planning regulations in Toronto are limiting new housing in the city. BCA responded to my request to come up with an architectural solution.

The most efficient way to add more housing would be with low-rise apartment buildings, what’s often called the “missing middle.” But that would be opposed by city planners and, almost certainly, neighbours and their city councillors. So I asked BCA to try something that might be more palatable. We chose at random a site near Bloor and Christie Streets that’s currently occupied by two semi-detached houses. The challenge: to add more good-quality housing units here, while roughly maintaining the visual rhythm and scale of the street.

Each of the units' floorplans provides an obvious contrast to the the long-and-skinny floors of a Victorian or Edwardian Toronto house, with a smaller proportion of wasted space and better light.

Click here for Link

7. Globe and Mail: Interesting Solutions at Yonge and Temperance Streets

Dave LeBlanc

How Toronto

For those who cry, “Toronto doesn’t respect its architectural heritage,” here’s a little story. A tale of moving heaven and earth – well, actually, brick, mortar, silicone moulds and some glass fibre-reinforced concrete – to create a heritage gateway at Yonge and Temperance Streets.

This tale also involves a ghost (albeit a friendly architectural one) and a developer who didn’t blink at some creative, costly solutions.

The "ghost facade."

ERA ARCHITECTS

It all started in the late 1980s, when a noticeable shift occurred in how to treat those nasty heritage buildings that often got in the way of progress. At about the same time as the façade of the 1898 Wood Gundy building was being incorporated into the north wall of Scotia Plaza, and the nearby Robert Fairweather façade at 100 Yonge St. was being saved in situ, plans were drawn up to save the old Aikenhead’s Hardware building – formerly the Comet Bicycle Co. – on Temperance Street.

Aikenhead’s, a lovely, 1894, classical brick pile by E.J. Lennox (with alterations carried out in 1905), would be moved 120 feet east of its original location at 17 Temperance to make way for the Bay-Adelaide Centre (which would stall in the early 1990s recession and leave nothing but a “tombstone” elevator shaft for years – but that’s another story).

While nothing would happen for quite some time, the seeds for a heritage gateway had been planted.

In the autumn of 2011, the decaying-yet-beautiful 1897 Dineen Building (hats and furs were its specialty) at 2 Temperance St. was purchased by visionary developer Commercial Realty Group; by spring 2013, caffeine lovers were lining up at Dineen Coffee Co. and marvelling at the interior’s restored iron columns.

That set the stage for what happened next. “The idea was there could actually be a little nub of cute heritage buildings right at the corner of Temperance and Yonge,” said ERA Architects’ Michael McClelland, who, along with KPMB and Adamson Associates, has been working with Brookfield Properties on the Bay-Adelaide Centre since 2012.

Click here for Link

8. Bay Today: ONTC Building in North Bay Changing Hands

Bay Today Staff

Historic ONTC building back on the market

Built in 1905, the old building formerly housed the Temiskaming & Northern Ontario Railw

The historic former Temiskaming & Northern Ontario Railway headquarters is up for auction.

One of North Bay's most notable buildings is back up for sale.

Ontario Northland has put 195 Regina back on the market. It was sold by auction in April, however, the company says the parties were unable to achieve an unconditional agreement for the purchase of the property.

See: Bidding ends today for historical ONR building

Built in 1905, the old building formerly housed the Temiskaming & Northern Ontario Railway (T&NO) general office and most recently the Ontera/ON Telcom offices.

The 9,559 square foot building has been vacant since 2015 but ONR officials say it has been maintained since then and remains in good condition. It also has been a popular filming location the past couple of years.

An open house will be held on Friday, August 17 and Ontario Northland is accepting offers on the building until the end of August.

Click here for Link

9. CBC.ca: North Buxton Church

Flora Pan

North Buxton suing for ownership of historic church tied to Underground Railroad

North Buxton suing for ownership of historic church tied to Underground Railroad

The congregation was ordered to leave the 152-year-old church in June this year

Flora Pan · CBC News · Posted: Aug 02, 2018 9:07 PM ET | Last Updated: August 2

The North Buxton church, located in a community west of Chatham-Kent, is right next to a cemetery which is the final resting place for many community members' ancestors. (Google Maps)

North Buxton Community Church, a congregation started by slaves who escaped through the Underground Railroad, wants ownership of church land it's used since 1866.

The church group filed a statement of claim against the British Methodist Episcopal Church (BMEC), who currently holds the trust over the land.

The statement says as an alternative to ownership of the church, they would accept $1.5 million in addition to $500,000 in damages.

North Buxton says in the statement that since 2003, the group has invested $1.5 million of improvements into the property � including the installation of two HVAC units.

In 2003, the church congregation decided to break away from BMEC because it felt the denomination no longer served its community.

The church was started in the 1850s but built in 1866. The community church has proposed to buy the building or even rent it, but those options were taken off the table. (Submitted by Buxton Historical Society)

Land dispute

The congregation started in the 1850s with the Buxton Settlement, a southwestern Ontario community that originated with the arrival of slaves from south of the border.

Over the past century and a half, members of the church have been the caretakers of local Black history.

But in June this year, the congregation was ordered to leave the church by BMEC. In the statement of claim, the cemetery on the land is the main issue.

"To many of the community, the care of the cemetery is of much more concern than the actual church building itself," the claim says.

North Buxton had tried to purchase the church building or rent it, but couldn't come to an agreement with BMEC.

Carolyn Robinson-Dungy was raised down the street on a farm. Her great-grandparents, grandparents and parents are buried in the North Buxton cemetery. (Meg Roberts/CBC)

The lawyer representing BMEC, Michael Czuma, who was involved in ordering the congregation to leave, said there were "contentious" and "unpleasant" meetings between the church group and BMEC.

"We just haven't been able to deal with these people. Their view is that they've been looking after it. They don't want to follow any of our rules," said Czuma in June.

"That wasn't a position that we were prepared to accept."

Click here for Link

10. Windsor Square: Overview of North Buxton Church Situation

Kim Elliot

North Buxton Church Fight Heats Up

North Buxton Church Fight Heats Up

BY: KIM ELLIOTT 16 AUGUST 2018

The North Buxton Community Church, a place of peaceful worship, is at the centre of a battle of ownership pitting the congregation against the British Methodist Episcopal Church.

Photo by Ian Shalapata.

(NORTH BUXTON, ON) � Dating back to 1855, a small congregation of former slaves and their contemporary Afri-Canadian descendants have taken up spiritual sanctuary together in a village now known as North Buxton. Yet despite their 163 years of continuous Christian praise, worship, and fellowship the church is being pressured to vacate the physical sanctuary located on Shadd Road in the picturesque hamlet in Raleigh Township, southwest of Chatham.

Not only is the congregation, currently known as the North Buxton Community Church, feeling the squeeze to leave, they are also clinging to the cemetery ground surrounding it, where lay many of their ancestors.

The current saga has also drawn the ire of non-church members and extended family as well as the support other church groups from various denominations beyond the municipality.

Tamara Muise, whose maternal grandfather and other relatives took to social media to fervently draw attention to this cause and rally the troops. Her efforts, and those of a few others, resulted in the attendance of hundreds of supporters to the last planned Worship Service on Sunday, June 24. It was the last date prior to eviction.

The attendees were met with good news of biblical proportion from pastor Clarke. A Windsor lawyer, Steve Pickard, of Colautti, Landry, Pickford Law, caught wind of the church�s plight and offered his services pro bono.

The North Buxton school house was home to the first congregation of churchgoers until their own place of worship could be constructed.

Photo by Ian Shalapata.

Since that time he has dug into the church�s long dated history and unearthed that the British Methodist Episcopal Church, under which the church property and 18 others in the Ontario are designated, was being held in trust due to an act of incorporation dating back to 1913.

The Buxton Mission was founded as an outreach of the Presbyterian Church of Canada under the leadership of the Reverend William King, just prior to the US Civil War. The minister and a group former slaves from the US met for nearly 10 years in the local district school house before the congregation was able to build and support their own place of worship. St Andrews Presbyterian Church was formed with Rev King as their first pastor.

But, in the 1920s, the church�s congregation decided to join the United Conference and became known as the First Union Methodist Church. They met in what is now known as South Buxton.

Most Methodist churches established by former slaves were affiliated with the African Methodist Conference. The First Union Methodist Church was briefly a part of the AME before becoming a member of the British Methodist Conference in 1856.

Editor's Note:

I had the opportunity to attend the Homecoming in North Buxton over Labour Day weekend. I highly recommend it as way to get to know this remarkable community. Having the descendants of the original settlers, who run the museum, show you the collection of buildings and artifacts really brought the place to life.

Click here for Link

11. St. Thomas Times Journal: Redevelopment Proposal for Alma College Site in St. Thomas

Laura Broadly

Alma developer decries public feedback

The developer who plans to build three apartment buildings on the site of the former Alma College says he's discouraged by feedback the project received at a public meeting.

The developer who plans to build three apartment buildings on the site of the former Alma College says he’s discouraged by feedback the project received at a public meeting.

City council held a meeting Tuesday to give residents a final opportunity to comment on the proposal by Patriot Properties Inc. before councillors decide whether to apply to have an order imposed by a provincial planning tribunal lifted.

“It was a little discouraging,” Michael Loewith of Patriot Properties said of the meeting.

Loewith presented a new concept plan Tuesday for the development that includes an Alma College commemorative spire.

But the new concept doesn’t include a replica facade – something the tribunal ordered.

The plan does include three apartment buildings, historic entrance gates, heritage garden, Alma College square and the historic amphitheatre.

Loewith said he was caught off guard at the meeting when Russell Schnurr, chair of council’s municipal heritage committee and a planning professor at Fanshawe College, presented a concept plan with a replica facade.

Loewith said a replica facade is financially “unfeasible” because about 8,000 square feet of historic masonry would need to be recreated at a cost of about $5.1 million.

“If we’re forced to do what he’s created and what Fanshawe College has created, I guess on our behalf, for the city’s behalf, the project will not go through,” Loewith said.

Click here for Link

12. London Free Press: Designation of 172 Central Avenue, Home of Dr. Dr. Oronhyatekha

Megan Stacey

Co-owner slams recommendation to preserve London home of Indigenous doctor

|

| 172 Central Avenue, important for associative and design reasons |

A heritage battle is looming over a historic London property.

The compelling history behind a 136-year-old London home won over city politicians Monday night.

The planning committee voted unanimously to recommend a heritage designation for a two-storey brick house at 172 Central Ave., a move that would block its owners from knocking down the building, if approved by council next week.

The property was home to several notable Londoners, including Dr. Oronhyatekha (also known as Peter Martin), one of the first Indigenous medical doctors in the country. He built the brick, Italianate-style house on that property in 1882.

Ava Hill, chief of Six Nation of the Grand River, where he was born, urged politicians to protect the building.

“His stately home is a testament to his accomplishments and you should take the utmost care to preserve this historic building.”

Heritage planner Kyle Gonyou told politicians about the history of the home, noting there are no other tributes to its original owner in London.

The home was later occupied by Canadian painter Tony Urquhart.

Click here for Link

13. cbc.ca: Riverdale's Oldest House - High tech makeover

Alie Chiasson

One of Toronto's oldest houses enters the 21st Century with a high-tech makeover

The owners of a log cabin in Riverdale think the gadgets are great but history trumps tech

Don Procter and Beverley Dalys bought the Ontario cottage-style home across the street from Riverdale Park in 2000. They knew the 200-year-old history of the building and had to have it. (Richard Agecoutay/CBC News)

Wi-Fi-activated blinds, a fancy fridge and a robot vacuum are not enough to drown out what makes the house at 469 Broadview special.

The log cabin, which was built more than 200 years ago, is a glimpse back in time. But on Wednesday, it was propelled into the 21st Century, courtesy of a marketing campaign for Best Buy to show that any home can benefit from the latest gadgets.

"When you live in this house you start to feel like a pioneer," said homeowner Don Procter.

He and his wife Beverly Dalys bought the home in 2000. It was rather dilapidated when they first saw it.

The remnants of a log cabin built by Revolutionary War veteran John Cox stands at the back of the Ontario cottage-style house. (Richard Agecoutay/CBC News)"The agent came running out and said, 'Stop, don't come any further this house is not for you!'"

But the two history buffs knew there was a centuries-old story behind the white and green plaster walls

"Bev and I looked at each other and we're like, 'are you kidding? this is for us!" said Procter.

Home to a high-ranking soldier

Around 1807, when Toronto was still the Town of York, and the nucleus of the primitive city was starting to develop around Fort York, John Cox, a veteran of the American Revolutionary War, was building his cabin in the woods.

"For a house on what's now Broadview Avenue it would have been quite rural," said historian Chris Bateman with Heritage Toronto.

Cox was one of many American soldiers who petitioned for land to start again in a new country.

John Cox was granted Lot 14 in the Town of York sometime in the late 18th century. The downtown core of early Toronto was developing south-west of his land, which would have been quite rural."Basically, soldiers could put in a request to the government and say, 'I did my bit for the crown and I should be rewarded," Bateman said

Cox died not long after the cabin was built and its later owners plastered over most of the logs to create the green and white cottage it stands as now.

Click here for Link

14. Apollo: New York City's Preservation System

Julia Vitullo-Martin-forwarded by Rob Hamilton

Does the system for protecting historic buildings in New York still work?

Illustration by Graham Roumieu/Dutch Uncle

The recent controversy over the expansion of the Frick has been resolved to general satisfaction, but wider questions surrounding the preservation of historic buildings and sites in New York remain.

When the Frick Collection decided in around 2013 that the easiest way to obtain much-needed space would be to build a 60,000-square-foot addition in their Russell Page-designed garden, it must surely have known there would be an uproar from preservationists, landscape architects, the media, and their immediate neighbours on the Upper East Side.

Now things are calmer. This spring the Frick put forth a more modest expansion plan which, despite some serious opposition, made its way through the politically charged land-use-review process that includes input from the local community board and approval from the Landmarks Preservation Commission, a city government agency. (Crucial as the commission is, it’s not the end of the road for the Frick, which must face the city’s Board of Standards and Appeals – and more public hearings – on three requested waivers in September.)

But what can be learned from this expensive controversy that in some ways began decades ago, in the 1970s, when the Frick was forced to postpone an expansion for economic reasons? Since 1935, the Frick has added only 700 square feet of space, a minuscule amount, even as its collection has more than doubled in size and its attendance has ballooned, thanks to booming tourism. It needs space to serve its patrons, who are often left standing in long lines outside and then excessively crowded once they gained admittance. Similarly, the museum store and café are tiny and inadequate, and the office space dark and cramped.

One of New York’s loveliest buildings, designed by Carrère and Hastings and sited amid serene gardens, the Henry Clay Frick residence houses an extraordinary art collection that includes some of the most famous paintings on the planet: Hans Holbein’s Thomas More and Thomas Cromwell, grimly facing each other across the fireplace, just as Frick had placed them; a roomful of Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s Progress of Love panels; three gorgeous Vermeers, full-length Whistlers and Van Dycks, many Rembrandts, and much more. Although well endowed financially, the Frick is small by New York standards. Its smallness, long part of its charm, is becoming a burden.

Click here for Link

15. CBC.ca: Scottish Castle for sale with Canadian Connection

Stephen Hunt

Castle that gave Calgary its name hits the real estate market

Regal home with a colourful history off Scotland's west coast can be yours for $1.2 million

Calgary Castle is an "exceptional" castle "overlooking the white sands of Mull's Calgary Bay," according to the listing provided by Edinburgh realtors Strutt and Parker.

It's on the market with a floor price of around $1.2 million, or 695,000 pounds.

Calgary Castle is an 'exceptional' castle 'overlooking the white sands of Mull's Calgary Bay,' according to the listing provided by Edinburgh realtors Strutt and Parker. (Strutt and Parker)

The castle, originally built in the 1700s and renovated in the 19th century by merchant navy captain Alan MacAskill, features a crenellated parapet, angled turrets, gothic-style windows and plenty of period details.

Click here for Link

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/ECMOBO6KGBAVDPS5LMBEJSZCXE.jpg)

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/VJW5ZVEV5JFM7PVE5FDOTDEHLU.jpg)

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/3NDSQT6LO5EPVMH5FRSA6SXNYE.JPG)

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/QDSCEH3C4ZCWNCIHXX7HIUGWRM.JPG)